OER 101

Welcome to How to use Open Educational Resources, a self-paced workshop.

Introduction

Greetings!

Welcome to How to use Open Educational Resources, a self-paced workshop.

So, what is this course all about?

This course walks you through techniques to incorporate Open Educational Resources (OER) into your teaching practice. The course will cover the fundamental aspects of OER including open licensing and public domain. It focuses on providing practical guidance in locating and applying openly available resources. It is expected that upon completion of this course participants will be able to

| Theme | Learning Objectives |

|---|---|

| Copyright/Licensing | Differentiate among open licensing, public domain, and traditional (“all rights reserved”) copyright. |

| Copyright/Licensing | Distinguish between the different types of Creative Commons licenses and their permissions. |

| Defining OER | Define open educational resources (OER) and explain their purpose within teaching and learning. |

| Finding OER | Locate open educational resources using major OER repositories and search strategies. |

| Adopting OER | Apply an appropriate Creative Commons license to one’s own work. |

| Adopting OER | Provide proper attribution for works shared under Creative Commons licenses. |

| Adopting OER | Recognize the benefits and challenges of adopting and adapting OER in educational contexts. |

This training is not facilitated. It is designed to to be a self-paced course. If you are interested in a facilitated training that will result in an official certificate upon successful completion, visit the SBCTC training website.

Good luck, have fun, and keep pushing yourselves!

Questions about the training? Email bchae@sbctc.edu.

Copyright & License

Before we start talking about Open Educational Resources (OER), let’s briefly discuss the concepts that provide a foundational context to understanding OER, Copyright & License.

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| What is copyright? | Copyright is a type of intellectual property law that gives creators exclusive rights to their original works of authorship. These rights include reproducing, distributing, performing, displaying, and creating derivative works from the original. |

| When is my work protected? | Your work is protected by copyright the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form of expression that can be seen, heard, or otherwise perceived directly or with the aid of a machine or device. The work must exist in some physical or digital form, even briefly. For example, notes written on paper or a file saved on a computer. |

| What does copyright protect? | Copyright protects original works of authorship such as literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, including books, articles, films, songs, software, photographs, and architecture. It does not protect facts, ideas, procedures, methods, systems, processes, concepts, or discoveries. It only protects the specific way those ideas are expressed. Copyright covers both published and unpublished works. |

| Should I register with the U.S. Copyright Office to be protected? | No. Copyright exists automatically once a work is created and fixed in a tangible form. Registration is not required for protection, but it is required to bring a lawsuit for copyright infringement involving a U.S. work. Registration also provides legal benefits such as eligibility for statutory damages and attorneys’ fees. Many creators register to establish a public record of their copyright ownership. |

This content is drawn from:

- The United States Copyright Office, Copyright.gov, the public domain.

- Copyright and Fair Use, Stanford University Libraries, CC BY-NC

Understanding OER

We will start the lesson discussing what open educational resources are. Please watch the video first and read through the content. It is important to understand the concept of open educational resources as it will be the base for the rest of the modules.

What (on earth) are “OPEN” educational resources?

Password- OER-HD (with Caption) from OpenWa on Vimeo, CC-BY

Have you ever found something from the internet that could be a perfect resource (image, video, quiz, etc.) for your course, and you spent hours trying to figure out the copyright issues with that resource? You couldn’t find any Terms of Use, and there was no author information, so you didn’t know who to contact to get the permission?

Wouldn’t it have been nice if that resource somehow said “I’m free to use, no strings attached, you don’t need to ask for my permission because it is already granted”?

Open Educational Resources (OER) are an answer to that need.

There are millions of educational resources out there that are available for others to freely use. There are all kinds: full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and many other tools, materials and techniques used to support access to knowledge.

Here is how OER is defined in more specific and fancy terms:

Open educational resources (OER) are educational materials that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others (definition by Hewlett Foundation).

To put it another way. OER meet these criteria in:

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Format | Materials in any medium, digital or otherwise. |

| Conditions | Works that either reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license. |

| Nature | Permits free use and re-purposing by others. |

To see how others define OER, please visit What is OER by Creative Commons.

Now that we’ve had a chance to discuss the concept of OER let’s dig a bit deeper. We’ve just learned that, in order to be an OER, the resource should be either in the public domain or released with an open license. Let’s talk about what the open license and public domain mean in the next Modules.

Open License

What is an open license?

If you recall, in the Copyright & License module, we explained that a license is permission granted by the copyright owner to use their work.

An OPEN license is a type of license that allows anyone to access, reuse, and share a work with few or no restrictions. To see how this differs from a traditional all-rights-reserved copyright, look at the comparison below.

| Type | Copyright Status | What can Others do? | Need Permission? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open License | Copyright retained by the author. | Others can use, copy, or adapt the work if they follow the license terms (for example, give credit). | No. Permission is already granted through the license. |

| All Rights Reserved | Copyright retained by the author. | Others may read or view the work but cannot copy, distribute, or change it. | Yes. You must ask the author permission. |

Where did it all start?

Let’s look at how the concept of open licensing began. You may have heard of an open source license, a type of license for computer software that allows source code to be used, modified, and shared under specific terms.

The free software movement launched in 1983. Since then, developers around the world have been creating and sharing open source code under clear, standardized licensing systems. Over time, other open licenses were developed in related areas, such as:

How Did Open Licensing Expand Beyond Software?

In 2001, inspired by the success of open source software, a group of educators, technologists, legal scholars, investors, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists came together to design a similar system for creative works that were not software, such as blogs, photos, films, and books.

They founded a nonprofit organization called Creative Commons, which released the first set of open licenses in 2002. These Creative Commons licenses made it easy for creators to share their works online while clearly stating how others could use them.

In summary

Many types of open licenses exist today, each developed for different areas of knowledge and creation. Among them, Creative Commons licenses are the most widely used for sharing materials that are not software code, such as blogs, photos, films, and books allowing creators to easily and legally share their work with the world.

Public Domain

In Module 2, we discussed that in order for an item to be eligible to be an open educational resource it has to be openly licensed or in the public domain. Through module 3 to module 5, we learned what it means to be released with an open license and how to apply it to your work. In this module, we will discuss public domain.

What is the Public Domain?

A public domain work is a creative work that is not protected by copyright, which means it’s free for you to use without permission. Works in the public domain are those whose intellectual property rights have expired, have been forfeited, or are inapplicable.

Why does something fall into the public domain?

| Cases | Description |

|---|---|

| Case 1: The copyright has expired. | U.S. copyright lasts 95 years from the date of publication for works published between 1924 and 1977. As of January 1, 2025, the public-domain cutoff date in the U.S. is 1929. In other words, copyright has expired for all works published in the U.S. before January 1, 1929. Each January 1 (“Public Domain Day”) a new year’s worth of works enters the public domain. |

| Case 2: The copyright owner failed to follow copyright renewal rules. | Under the 1909 Copyright Act, works published in the U.S. between 1924 and 1963 were initially protected for 28 years. To keep protection for a second term, the owner had to file a renewal in the 28th year after publication. If renewal was not filed, the work immediately entered the public domain. Most works from this period were never renewed and are now public domain. |

| Case 3: The copyright owner deliberately places the work in the public domain. | An author can choose to waive copyright and dedicate a work to the public. Common wording includes “This work is dedicated to the public domain.” This is relatively rare. Today, creators often use tools such as the Creative Commons CC0 Public Domain Dedication, which provides explicit legal language for worldwide use. |

| Case 4: Copyright law does not protect certain works. | Short phrases, names, titles, and slogans (for example, “Show me the money”) are not protected by copyright because they lack authorship and creativity. Facts, ideas, systems, methods, and scientific discoveries are also not protected, though a particular expression of them can be. U.S. Government works created by federal employees in the course of their official duties are automatically in the public domain. |

How do I determine if a work is in the Public Domain?

Using the cases described above, the table below outlines practical steps for determining whether a work is in the public domain.

| Steps | Examples |

|---|---|

| Step 1. Locate the work’s publication date and see if it was published before 1929. If it was, the work is automatically in the public domain. | The Great Gatsby (novel, 1925) by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mrs. Dalloway (novel, 1925) by Virginia Woolf, and Metropolis (film, 1927) are all public domain. |

| Step 2. Check the renewal records for works published between 1924 and 1963. If the copyright was not renewed, the work is now in the public domain. | Many mid-century science textbooks and technical manuals were never renewed and are now public domain, while Animal Farm (1946) was renewed and remains under copyright. |

| Step 3. Determine whether the work is a U.S. government publication. Works created by federal employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. | U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Publications, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Datasets, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Reports are all public domain. |

| Step 4. If none of the above apply, do additional research. Use Peter Hirtle’s Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States (Cornell University). | A 1950 university dissertation (Many dissertations from that period were never formally “published.” Under U.S. copyright law, unpublished works follow different rules: protection lasts for the author’s life plus 70 years (not a fixed term based on publication year). |

What is the difference between public domain, open license, and all rights-reserved copyright?

It is important to understand the difference among these three legal conditions that determine how creative works can be used.

Under all rights-reserved copyright, the creator or copyright holder retains full control over the work. Others may not copy, share, or modify the material without explicit permission. This is the most restrictive copyright condition.

An open license still recognizes the creator’s copyright ownership but allows others to use, share, and sometimes adapt the work in advance under specified terms (for example, requiring attribution or limiting commercial use). Users must follow the license conditions, including crediting the creator when required.

In contrast, public domain works are not protected by copyright, either because the copyright has expired, was never applicable, or has been deliberately waived by the creator. Anyone can use, reproduce, or modify these works freely, without needing permission or giving credit. In that sense, the public domain represents the purest form of open access to creative materials (the phrase "purest form" is from Public Domain, CC-BY).

See the table below to see the difference between open license, public domain and all rights reserved copyright.

| Type | Copyright Status | What can Others Do | Need Permission? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Domain | Copyright waived or expired. | Anyone can use, copy, or change the work freely. | No. Credit is appreciated but not required. |

| Open License | Copyright retained by the author. | Others can use, copy, or adapt the work if they follow the license terms (for example, give credit). | No. Permission is already granted through the license. |

| All Rights Reserved | Copyright retained by the author. | Others may read or view the work but cannot copy, distribute, or change it. | Yes. You must ask the author permission. |

The content in the table above is also available as an infographic.

If you want more in-depth discussion about public domain, check out The Public Domain by James Boyle, or The Public Domain by Rich Stim. You can also check out a Creative Commons–licensed comic that explains the concept in a fun and accessible way: Tales from the Public Domain.

Finding OER

We’ve created a comprehensive “Find OER” feature on our site designed to meet all your needs in one place. It offers a categorized search guide for all types of OER, with resources organized to help you easily find and choose materials that best fit your goals. Scroll down to explore how to find Creative Commons licensed videos, images, course materials, and textbooks, and learn how to properly attribute them.

How to find a CC licensed video

Watch this quick demo to see the process in action. You can also review the same content in Google Slides.

How to find a CC-licensed image

Watch this quick demo to see the process in action. You can also review the same content in Google Slides.

How to find CC-licensed course material:

Watch this quick demo to see the process in action. You can also review the same content in Google Slides.

How to find an open textbook:

Watch this quick demo to see the process in action. You can also review the same content in Google Slides.

How do I attribute a Creative Commons licensed work?

Watch this quick demo to see the process in action. You can also review the same content in Google Slides.

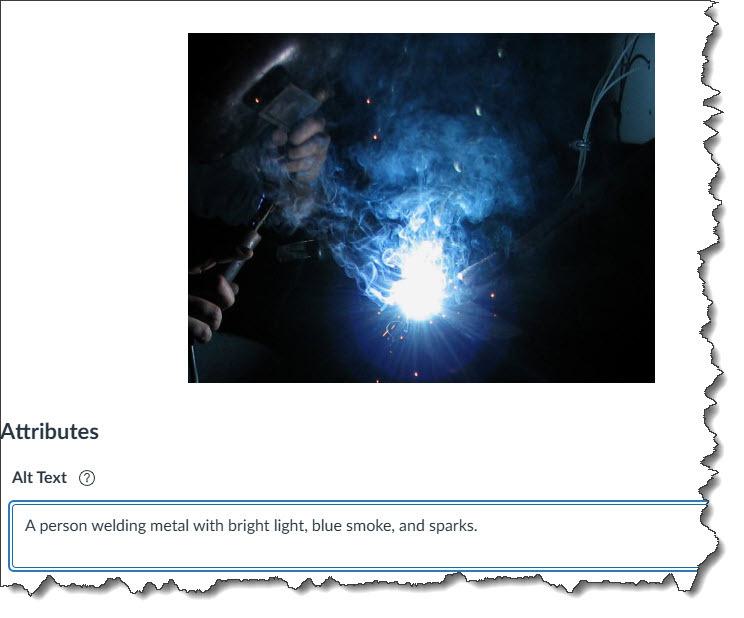

Example Ideal Attributions

| Examples of Ideal Attribution | Why |

|---|---|

| Welding by rawdonfox is licensed under CC BY. | Title: The title of the work, “Welding,” is clearly noted. Author: The author, “rawdonfox,” is properly credited and linked to the creator’s Flickr profile page. Source: The source, “Welding,” is linked directly to the original Flickr page where the work was first published. License: The license, “CC BY,” is clearly identified and linked to the official Creative Commons Attribution license deed. |

| Module 4: Protein Structure by Open Learning Initiative is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA. | Title: The title of the work, “Module 4: Protein Structure,” is clearly noted. Author: The author, “Open Learning Initiative,” is properly credited and linked to the project’s main page. Source: The source, “Module 4: Protein Structure,” is linked directly to the original course content page. License: The license, “CC BY-NC-SA,” is clearly identified and linked to the official Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–ShareAlike license deed |

| This work, “Pipe Fabrication Welding”, is a derivative* of Welding by rawdonfox used under CC BY. Pipe Fabrication Welding is licensed under CC BY by Boyoung Chae. | Title, Original Author, Source, and License: All key attribution elements are clearly noted, ensuring that proper credit is given to the creator. Derivative* Work Statement: The attribution explicitly states that this piece is a derivative work, clarifying that it has been adapted or modified from the original. New Author: The creator of the derivative work is properly identified and credited as the new author, acknowledging their creative contribution while still respecting the rights of the original author. |

| Welding by rawdonfox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License. | Title, Original Author, Source, and License: All key attribution details are clearly included in the offline document, ensuring proper credit is maintained even without an online link. License Type and URL: The full Creative Commons license name and URL are written out in the text so users can understand the licensing terms without needing a hyperlink. |

Example of Incorrect Attributions

| Examples of Incorrect Attribution | Why |

|---|---|

| Elephant Photo: Creative Commons Licensed. | Author is not noted. Creative Commons is not the author of this photo. There is no link to original photo. There is no mention of the license, much less a link to the license. “Creative Commons” is an organization. |

| This work, “Green Banana”, is a derivative* of “Banana!” by Graham Reznick used under CC BY-NC-ND “Green Banana” is licensed under CC BY by Boyoung Chae. | There is no link to original photo. The original photo was released under CC BY-NC-ND, which means that the user is not permitted to distribute the modified material. |

*Derivative Works: A derivative work is a work based on or derived from one or more already existing works. Common derivative works include translations, musical arrangements, motion picture versions of literary material or plays, art reproductions, abridgments, and condensations of preexisting works. Another common type of derivative work is a “new edition” of a preexisting work in which the editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications represent, as a whole, an original work. To learn more about Derivative works, please read Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations by US Copyright office.

For example, the IGNIS logo (on the right) is a derivative built from the original lightning image (on the left).

| Original Image | Derivative |

|---|---|

|  |

To learn more about Derivative works, please read Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations by the US Copyright office.

For more guidance on attributing a Creative Commons licensed work, please visit CC Wiki-Best Practices for Attribution.

Attributing Works with Different Licenses

When you combine or include materials under different Creative Commons (CC) licenses within your own work, it’s important to clearly indicate how each part is licensed and ensure you’re respecting the original terms.

For example, if your content is mostly CC-BY but you have incorporated CC-BY-SA materials into your work. Should you mark your work with CC-BY-SA?

Generally, it is okay to collect works under CC licenses, as long as the attributions are clear, and there is a note in the material that mentions that some material might have more restrictive licenses.

You could simply add “Except otherwise noted” in the main CC license notice, which indicates that the materials might contain some resources governed by different terms and should therefore be treated as specified by the original author. Or you could add a more specific note: “Original material in this course is licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license; however, please respect more restrictive licenses of adopted content where attributed.”

Therefore, regarding this case, you can still release your work under a CC BY license with the added phrase “Unless otherwise noted” in the licensing notice. This means the content is CC BY licensed but it contains some resources that are marked with different licenses, such as CC BY-SA, and those resources should be treated as specified by the original author intended.

The exception would be in the case of adapting the BY-SA materials. Any adaptations would have to be shared alike under the same license (BY-SA) per the ShareAlike condition (Links to an external site.). But if the BY-SA materials are included verbatim, faculty need only make note of those materials and the separate licenses governing those materials.

Keep in mind that you can only ever CC license rights to work that you own. In general, please make it a practice to clear all copyright issues (Links to an external site.) before releasing your work with a CC license. In order to avoid distributing copyrighted work, faculty should make a practice of stripping their courses of copyrighted material before sharing to the Commons.

The following table summarizes these guidelines for quick reference.

| Situation | What to Do | Notes/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| You’re creating a new work (e.g., textbook, course, website) and most of your content is under CC BY, but you include materials with other CC licenses (e.g., CC BY-SA, CC BY-NC) | You can still license your work under CC BY, but include a note such as “Unless otherwise noted” to indicate some materials may have different, possibly more restrictive, licenses. | Example: “Original material in this course is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license; however, please respect more restrictive licenses of adopted content where attributed.” |

| You incorporate CC BY-SA materials without modifying them (use as-is) | You do not need to apply CC BY-SA to your entire work. Just make sure to provide full attribution and clearly identify the specific section/resource with its license. | Example: A video or diagram embedded under CC BY-SA remains CC BY-SA, while the rest of your course can stay CC BY. |

| You adapt or modify materials licensed CC BY-SA | Your adaptation must be licensed under the same license (CC BY-SA) because of the ShareAlike condition. | The ShareAlike rule applies only to modified content, not to entire collections. |

| You include copyrighted materials or unclear ownership items | You cannot apply a CC license to materials you don’t own or have rights to. Always remove or replace copyrighted material before publishing your work. | Good practice: “Strip” all copyrighted materials before sharing to a commons or repository. |

Creative Commons Licenses

What are Creative Commons Licenses?

People often say “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Sometimes, a well-made video is worth a million words and then some. To understand Creative Commons Licenses, first, watch this video that explains the basics behind Creative Commons licenses.

Creative Commons Kiwi by plccanz, CC-BY

Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that enables the sharing and use of creativity and knowledge through free legal tools. Their free, easy-to-use copyright licenses provide a simple, standardized way to give the public permission to share and use your creative work — under conditions of your choice. CC licenses let you easily change your copyright terms from the default of “all rights reserved” to “some rights reserved.” (Definition from Creativecommons.org)

There are 4 Key license elements:

| Icons | License | Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| BY | Attribution: You let others can copy, distribute, perform and remix your work if they credit your name as specified by you. | |

| ND | No Derivatives: You let others copy, distribute, display and perform only original copies of your work. If they want to modify your work, they must get your permission first. | |

| SA | Share Alike: You let others copy, distribute, display, perform, and modify your work, as long as they distribute any modified work on the same terms. If they want to distribute modified works under other terms, they must get your permission first. | |

| NC | Non-commercial: You let others copy, distribute, display, perform, and (unless you have chosen NoDerivatives) modify and use your work for any purpose other than commercially unless they get your permission first. |

Creative Commons Licenses

CC licenses are combinations of these elements. There are 6 CC licenses:

| License icon | Attribution | License Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Attribution (CC BY) | This license lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work, even commercially, as long as they credit you for the original creation. This is the most accommodating of licenses offered. Recommended for maximum dissemination and use of licensed materials. |

| Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND) | This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to you. |

| Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) | This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms. |

| Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) | This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work even for commercial purposes, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms. This license is often compared to “copyleft” free and open source software licenses. All new works based on yours will carry the same license, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use. This is the license used by Wikipedia, and is recommended for materials that would benefit from incorporating content from Wikipedia and similarly licensed projects. |

| Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) | This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge you and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms. |

| Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) | This license is the most restrictive of the six main licenses, only allowing others to download your works and share them with others as long as they credit you, but they can’t change them in any way or use them commercially. |

The above text from “About the Licenses” by Creative Commons is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

To learn more about license designs, rationale, and structure of Creative Commons licenses, please read About the licenses by Creative Commons.

How can I apply a Creative Commons license to my work?

Watch this quick demo to see the process in action. You can also review the same content in Google Slides.

Accessibility

An Overview of Accessibility

As instructors, we have legal and ethical obligations to ensure our courses are fully accessible to all learners, including those with disabilities. We use digital resources in our courses because we believe they enhance learning. However, unless carefully chosen with accessibility in mind, these resources can have the opposite effect for students with disabilities, erecting daunting barriers that make learning difficult or impossible. For example, consider the accessibility challenges students described below might face.

Students who are deaf or hard of hearing are unable to access the contents of a video presentation unless it’s captioned.

Students who are blind or visually impaired use assistive technologies such as audible screen reader software or Braille devices to access the content of websites, online documents, and other digital resources. They depend on authors providing alternate text that describes the content of images as well as headings, subheadings, lists, and other markup that helps them understand the structure and outline of the resource.

Some students who have learning disabilities such as dyslexia use assistive technologies that visibly highlight digital text as it’s read aloud; and are therefore dependent on text being readable (as opposed to a scanned image).

Students who are physically unable to use a mouse are unable to use interactive web and software applications unless these applications can be operated with a keyboard.

Students who are color blind may be unable to understand content that communicates information solely using color (for example, a bar chart with color as the sole means of differentiating between the bars).

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0, developed by the World Wide Web Consortium, provide an international standard that defines accessibility of web-based resources. The principles of WCAG 2.0 are applicable to other digital assets as well, including software, video, and digital documents. The University of Washington has developed an IT Accessibility Checklist that can help anyone creating or choosing digital resources to understand the accessibility requirements related to the features and functions of those resources.

The rest of this module provides tips for ensuring that the resources you’re choosing for your course are accessible to all learners.

Choosing and Using Accessible Video

When selecting video, be sure to choose videos that include closed captioning. Closed captions provide a text version of the spoken audio and other critical sounds, displayed in sync with the video.

Closed captions make video accessible to students who are deaf or hard of hearing, but also benefit many others: They help second-language students understand the spoken audio; they help all students learn the spelling of the words that are being spoken; they make it possible to search the video for specific content; and they can be repurposed as an interactive transcript, which is a great feature for everyone!

Captions are supported by all major video hosting services including YouTube and Vimeo. If a video is captioned, it will have a CC button on the video player.

YouTube automatically captions most videos that are uploaded to its website. However, automatic captions, which are created by a computer, are not accurate enough to be relied upon (consider the effect of one missed “not” on the meaning of the video). To check whether a video has reasonably accurate captions created by humans, click the CC button on the video player to turn captions on, and watch a few short segments of the video.

Consult the following resources for additional information on finding videos that have captions:

If you find an open-licensed YouTube video that is perfect for your course but does not currently have captions, caption it! Here’s how:

Choosing and Using Accessible Images

If images are used to communicate information, they should include short text descriptions for individuals who are unable to see the images. These short descriptions are typically referred to as “alternate text” or “alt text.”

Most authoring tools that support adding images to content also support adding alt text to an image. When you’re adding an image to a web page or document, simply look for an “alt text” field in the Image Properties dialog and enter a short description into the space provided.

The alt text that you enter for a particular image depends on the context. Think about what you’re wanting to communicate by adding the image. Then, add alt text that will communicate the same idea to someone who is unable to see the image.

The following resources provide additional guidance for writing good alt text.

- WebAIM: Alternate Text

- Write helpful Alt Text to describe images (Harvard University)

If the image contains important detail than is too complex to be described in one or two brief sentences (for example, a chart or graph) then the text description will need to be provided separately from the image, either within surrounding text on the same page, or on a separate page that is accessible via a link on the main page.

Choosing and Using Accessible Course Material

When choosing among the wide variety of course materials that are available from the sources listed on our Course Materials page, be sure to consider whether these materials might present challe

nges or barriers for students with disabilities. Ask specific questions, such as:

- Is all written content presented as text, so students using assistive technologies can read it?

- If the materials include images, is the important information from the images adequately communicated with accompanying alt text?

- If the materials include audio or video content, is it captioned or transcribed?

- If the materials have a clear visual structure including headings, sub-headings, lists, and tables, is this structure properly coded so it’s accessible to blind students using screen readers?

- If the materials include buttons, controls, drag-and-drop, or other interactive features that are operable with a mouse, can they also be operated with keyboard alone for students who are physically unable to use a mouse?

- Do the materials avoid communicating information using color alone (e.g., the red line means X, the green line means Y)?

If you find open course materials that are perfect for your course but you are unable to answer “Yes” to each of the above questions, contact the author and talk to them about accessibility! Your feedback may inspire them to improve the accessibility of their materials, which will benefit everyone!

Choosing and Using Accessible Textbooks

Most of the downloadable textbooks available through the sites listed on our Textbook Resources page provide textbooks in PDF format. PDF, like most other document formats, includes support for accessibility features such as headings, subheadings, lists, and alt text on images, but the author and/or publisher must make a conscious effort to include these features.

In order to support accessibility features, a PDF file must be tagged. A tagged PDF is a type of PDF that includes an underlying tagged structure that enables headings to be identified as headings, lists as lists, images as images with alt text, etc. Tags provide the foundation on which accessibility can be built. To determine whether a particular PDF is tagged, open it in Adobe Acrobat or Adobe Reader and go to Document Properties (Ctrl + D in Windows; Command + D in Mac OS X). In the lower left corner of the Document Properties dialog, “Tagged” is either “Yes” or “No.”

The following resources provide additional guidance for creating accessible documents, particularly in PDF, and on evaluating whether PDFs are accessible and if not, fixing their accessibility problems.

- University of Washington: Creating Accessible Documents

- Adobe: PDF Accessibility Overview

- WebAIM: PDF Accessibility

If you find an open textbook that is perfect for your course but is not accessible, contact the author and talk to them about accessibility!

For more information, visit the SBCTC Accessibility Center, where you’ll find resources and guidance to support web and IT accessibility awareness, understanding, and implementation across Washington’s 34 community and technical colleges. The site also features updates on events, trainings, policies, and additional resources.

Why OER Matters

We have discussed OER, Open Licenses, Creative Commons Licenses, and Public Domain through 6 modules. We learned that there are quality open resources made available for educators like us to adopt and adapt. In this module, we will discuss why all these matter to us (or not).

What are the benefits in using OER?

I purposely waited until the final module to ask this question: why on earth do we care? Why do open educational resources matter? What is the point of using OER?

The development and promotion of open educational resources is often motivated by a desire to curb the commodification of knowledge and provide an alternate or enhanced educational paradigm (sentence from Wikipedia, OER). As an educator, what benefits do you see in using OER for you and your students?

Below are some of the benefits of using open educational resources that I have seen while working with OER over the past several years.

Saves costs for students

OER can offer drastic savings in the cost of education. Some students, who otherwise cannot afford to buy expensive textbooks or other course materials, will appreciate this affordable option when taking your course. A faculty member from a community college said during an interview

“Many of my students are struggling. They are working adults trying to make ends meet. I used to use a $150 textbook from a publisher and I switched to an open textbook. My students love it because it costs nothing. They are now asking if my next course will use the free textbook too.”

“I made my own course materials package for my students. It is free to download and a printed version is only 40 dollars. I could not find a ready-made open textbook for my course. So I combined the open resources out there and developed my own. It was a lot of work, but my students are happy to save good money.”

Grants access to more quality choices

There are more than 1000 free online courses from leading universities that are open to the public. Students in low-resource environments can enjoy the recorded lectures and video tutorials developed by other institutions such as,

Open Yale courses (from Yale University),

Webcast.Berkeley (from the University of California at Berkeley),

Stanford Engineering Everywhere (from Stanford University),

Open Learning Initiative (from Carnegie Mellon University)

MIT OpenCourseWare (from MIT)

Open Learning Initiative (from Carnegie Mellon University)

Harvard Open Courses at Harvard Extension School (from Harvard University)

This is just to name a few. Many other universities, colleges, and other educational institutions in higher education are preparing to offer open online courses to the public. Educators are happily sharing their life’s work with students and enjoying the greater influence their materials have on larger audiences.

Helps prior learning and after learning

If an instructor opens his/her own course materials, and shares them with the public it greatly enhances opportunities for learning for both students who already took the course and the prospective students.

Students often would like to look over course materials before the term begins. If students have that opportunity to take a look at the course materials it will help them make more informed decisions in choosing their courses, and will give them the opportunity to prepare themselves for the class.

Students also would like to revisit their course materials after the quarter/semester is over to refresh their memories or to further study the topics. Open course materials will help them reinforce what they have learned and further develop their level of understanding in the area.

Provides peace of mind for all users

If you’re re-using someone else’s materials, one of the best reasons for using OER is for peace of mind about attribution. The resources are licensed to allow the sharing of content and so you will not need to contact the author about making use of his or her work provided that what you want to do falls within the ‘open’ license. OERs are free at the point of use, so you will not need to provide monetary compensation for using them. Then there is the opportunity of discovering alternative ideas for presenting and teaching your subject matter or being able to point your students to the alternative explanations for further study (text in this paragraph is from Why OER by Kabils, CC BY).

Other benefits

- Showcases research to widest possible audience

- Enhances a school’s reputation as well as that of the teacher or researcher

- Social responsibility – provides education for all

- Shares best practice internationally

- Creates additional opportunities for peer review

- Maximizes the use and increases availability of educational materials

- Raises the quality standards for educational resources by gathering more contributors

What do you see? Do they make sense? Think about what OER can do for you and your students.

What are the challenges in using OER?

Below are some of the challenges of using/providing open educational resources.

Quality Assurance

A growing number of digital resources are available. Teachers, students and self-learners looking for resources will not have trouble finding resources but might have a harder time judging their quality and relevance. Many institutions that supply OER go through an internal review process before releasing them to the public but these processes are not open in the sense that the user of the resource can follow them (text from Open Educational Resources by Jan Hylen, CC-BY). Also there is a lack of research data focusing on comparing the amount students learn from OER compared to the amount they learn from prevailing publisher materials. Whether the material is free or expensive, quality does matter.

Sustainability of OER

Many OER initiatives begun in recent years were dependent on one-time start-up funding. Although some projects have a strong institutional backing, it is likely that the initial funding will cease after a few years and maintaining the resources will be difficult and expensive. Without maintenance the resources will become obsolete and the quality could be lost. Therefore it is critical to figure out how to sustain these initiatives in the long run.

Lack of public understanding about OER

At just over ten years old OER is a very recent development in education. It requires a huge paradigm shift and attitude change and this is a much bigger challenge than introducing a new tool or knowledge. Many in education do not understand the potential of OER and feel that it threatens their ownership of intellectual property. It takes some time to understand that open licenses, such as Creative Commons licenses, clearly recognize and can reinforce someone’s intellectual ownership. The open licenses are simply to make the sharing process easy while protecting the copyright.

What other challenges do you see?

Below are presentation slides that discuss the benefits and challenges of OER prepared by Washington State Community and Technical College faculty.

- The Road Ahead Open Educational Resources Touting the Benefits while Recognizing the Challenges by Pat Pickering

- Open Educational Resources by Amy Hammons

- Open Educational Resources: Should I Use them? by Leo Hopcroft

- In Favor of Open Educational Resources by Bev Farb

- Open Educational Resources: Weighing the Benefits and Challenges by Debi Griggs

- OER: Benefits and Challenges by Tamara Ottum

- OER: The Good, The Bad by Nancy Scofield

- Pros and Cons of OER by Barbara Jacobs

- OER-The Future Picture of Online Education? By Tom Pickering

- Benefits and Challenges of Using OERs by Debbie Crumb